Wallflower: Choosing Function Over Fun

Overview

Wallflower is a digital toolkit for anxiety relief, targeting panic recovery, social anxiety, and confidence-building. Mid-project, I stepped up to lead both user research and UI design. By adopting an agile UX cycle and letting go of personal creative attachments, I helped the team pivot from overstimulating minigames to a calm, accessible app—with a 27% reduction in user-reported stress at launch.

🎯 Problem

Our team originally pitched Wallflower as a joyful “toybox” of minigames, puzzles, and playful nature animations to support anxious users. As a game designer, I joined the team excited to build those playful tools.

But early research challenged our assumptions.

Challenge:

Could we rethink Wallflower from a stimulating experience into a truly calming one—without losing appeal or accessibility?

🧭 My Role

Originally brought on for user research, I pivoted into lead UX designer mid-production, taking over both research and UI design responsibilities due to team bandwidth issues.

🔍 Research Process

1. Audience Definition

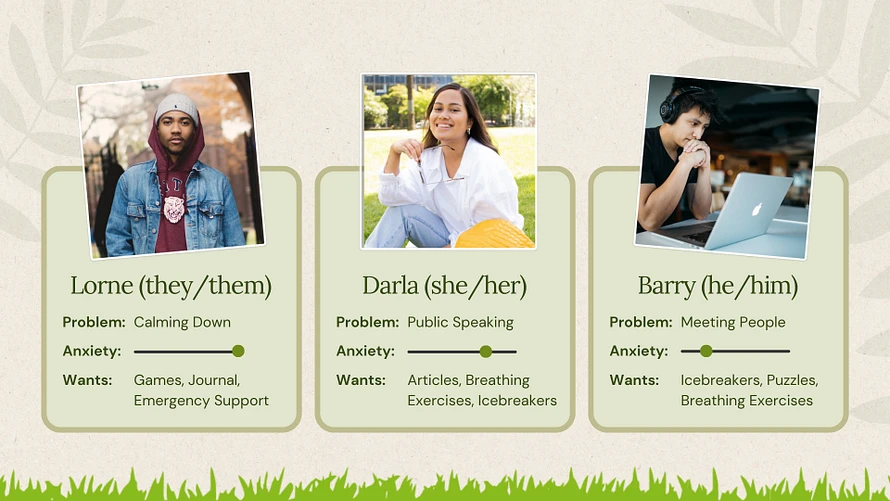

We focused on three high-need contexts:

-

Panic attack recovery

-

Social anxiety in daily life

-

Confidence building

Our user group was primarily college students navigating stress, identity, and emotional overwhelm—especially during high-pressure times like finals.

2. Biweekly UX Testing Loop

To manage scope and ensure quality:

-

I ran one-on-one usability tests every two weeks with ~5 users

-

Synthesized findings into a prioritized UX change proposal

-

Presented to stakeholders for feedback and approval

-

Implemented updates in Figma prototypes for dev hand-off

This became our core agile loop: research → recommend → iterate → build.

3. Emotional Safety Redesign

Early tests revealed that our toybox pitch—while creative—was overstimulating for anxious users. Many reported:

-

Decision fatigue

-

Confusion around navigation

-

Frustration with “cheerful” feedback loops during distress

This was a major turning point for me. As a game designer, I had to kill my darlings—cutting interactive features I loved—in order to respect user needs.

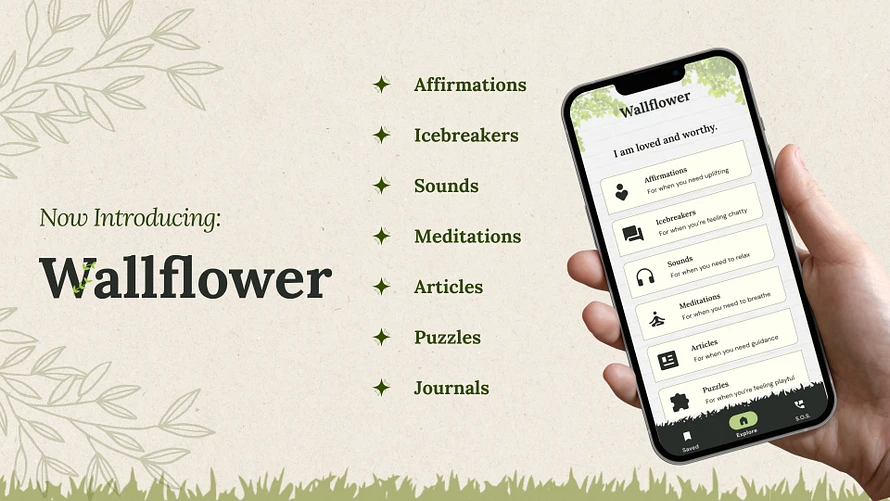

4. Key UX Pivots

-

Replaced saturated colors and microanimations with flat, neutral visuals

-

Prioritized low-effort content like guided meditations, affirmations, soft sounds, and journaling

-

Simplified flows to support users under high emotional load

-

Introduced emotional valence charts to track user mood across sessions

This was a moment of real growth: I learned to value effectiveness over novelty, and led our team toward calm by letting go of drama.

🧪 Final Validation

I proposed and ran a real-world A/B test to evaluate impact during finals season:

-

Initial survey: All users rated resting anxiety levels

-

Split into test group (with app access) and control group (no app)

-

After two weeks, follow-up survey measured change in anxiety

Results:

-

🎯 Test group reported 27% lower stress levels than control

-

✅ We verified not just usability—but emotional impact

-

🎓 This went above standard student project scope, but we felt it was ethically necessary to validate our work

💡 Outcome

-

Re-scoped Wallflower from toybox to toolkit

-

Designed and validated a calm-centered UX strategy

-

Completed on time despite major mid-project role pivot

-

Delivered a functioning app that measurably helped users cope with anxiety

🛠️ Tools & Skills Demonstrated

-

UX Research & Usability Testing

-

Agile Sprint Planning

-

UI Design & Prototyping (Figma)

-

Accessibility & Cognitive Load Reduction

-

Emotional Valence Mapping

-

A/B Testing & Experimental Design

-

UX Strategy & Scope Pivoting

-

Cross-functional Communication & Management